Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Genius in Motion, Myth in Shadow

Few figures in Western culture occupy the precarious space between historical fact and artistic myth as completely as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. To speak of Mozart is to invoke not merely a composer, but an idea: precocity bordering on the supernatural, beauty achieved with apparent ease, and a life extinguished before its full promise could unfold. Yet behind the legend stands a working artist—restless, disciplined, ambitious, and profoundly human.

The Child Who Heard the World in Music

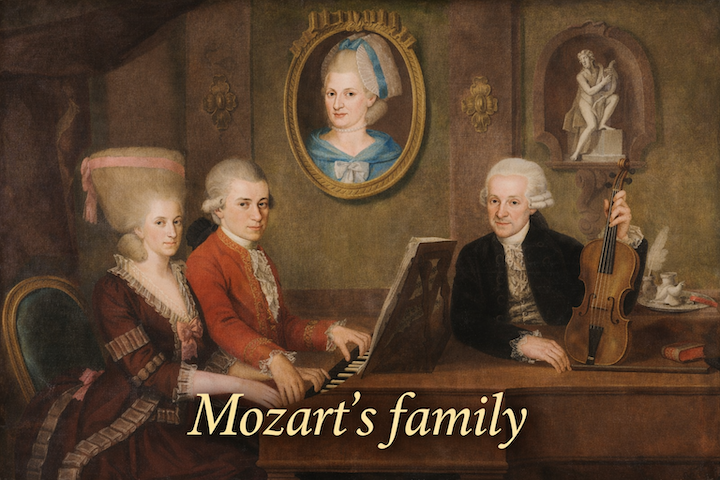

Born on January 27, 1756 in Salzburg, Mozart did not “learn” music so much as awaken within it. By the age of five, he was composing; by six, performing before European courts. His father, Leopold Mozart—violinist, pedagogue, and shrewd manager—recognized early that his son’s talent was not ordinary brilliance but something rarer: an instinctive grasp of musical structure married to an emotional fluency beyond his years.

The long tours of Mozart’s childhood—Paris, London, Mannheim, Milan—were both education and exhibition. They sharpened his ear to national styles and trained him in the social theater of patronage. They also exacted a cost. Even as a child, Mozart learned that genius alone did not guarantee security.

A Composer in Search of Freedom

Mozart’s early adulthood unfolded as a sustained act of resistance—against rigid hierarchy, against inherited authority, and against the suffocating expectations of court employment that reduced music to ornament and obedience. His break with the Archbishop of Salzburg in 1781 was therefore not merely a professional rupture, but an existential one. To remain would have meant safety at the cost of artistic truth. To leave meant freedom shadowed by risk.

Vienna promised independence, but it offered no guarantees. Without a permanent patron, Mozart was forced into the precarious life of a freelance composer—teaching, performing, composing at relentless speed. Freedom demanded self-reliance, and self-reliance exposed him to instability. Yet it was precisely within this tension that his voice matured.

Nowhere is this struggle more eloquently articulated than in the piano concertos of the 1780s. Mozart transformed the concerto from a display of virtuosity into a philosophical conversation—a drama of cooperation and conflict between the individual and the collective. The soloist no longer dominates; it listens, argues, yields, and asserts itself again.

- Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466 confronts darkness head-on, its stormy urgency admired by Beethoven for its emotional daring.

- Piano Concerto No. 21 in C major, K. 467 offers a contrasting vision: serenity without naïveté, its slow movement unfolding like time briefly at rest.

- Clarinet Concerto in A major, K. 622, written in Mozart’s final year, stands as a valedictory gesture—music that speaks not of triumph, but of warmth, reconciliation, and human tenderness.

In these works, freedom is not triumphant. It is negotiated. Mozart’s independence does not shout; it converses, revealing a composer who understood that autonomy, like music itself, exists only in relationship.

Music That Knows the Human Heart

Mozart’s mature style is often mistaken for lightness, as though clarity were synonymous with simplicity. In truth, his transparency conceals extraordinary emotional density. Joy and grief coexist without hierarchy; laughter is edged with vulnerability; beauty never denies suffering. His music does not exaggerate emotion—it recognizes it.

This emotional intelligence is most piercing in his operas, where Mozart grants full psychological reality to characters long treated as secondary or symbolic. Servants speak with moral authority. Women possess agency, irony, and desire. Outcasts are no longer caricatures, but mirrors held up to society itself.

- Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) dismantles social hierarchy through wit and musical equality, allowing human dignity to outsing aristocratic privilege.

- Don Giovanni is both seduction and indictment—a dark meditation on power, desire, and the inevitability of reckoning.

- Così fan tutte, often misunderstood as cynical, reveals instead a ruthless honesty about love’s fragility and self-deception.

- Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) unites fairy tale and Enlightenment philosophy, innocence and initiation, earthly trial and spiritual aspiration.

Mozart’s operatic world is neither moralistic nor sentimental. It is compassionate without illusion. He does not resolve human contradictions; he allows them to sing. In doing so, he affirms that emotional truth—however uncomfortable—is itself a form of beauty.

Taken together, these works reveal a composer who understood the heart not as a source of excess, but as a site of knowledge. Mozart’s music endures because it listens as much as it speaks—meeting the listener not above or beyond life, but squarely within it.

Sacred Music and the Question of Mortality

Mozart’s sacred music confronts mortality not with fear alone, but with theological honesty. Raised in Catholic Salzburg, Mozart absorbed the liturgy, doctrine, and ritual of the Church from childhood. Yet his religious music never functions as mere ecclesiastical obligation. Instead, it becomes a space where belief, doubt, hope, and human vulnerability coexist.

Unlike many composers who emphasize divine judgment or cosmic authority, Mozart approaches death as a deeply human passage—one that invites mercy rather than terror. His sacred works rarely thunder with dogma. They listen. They plead. They tremble.

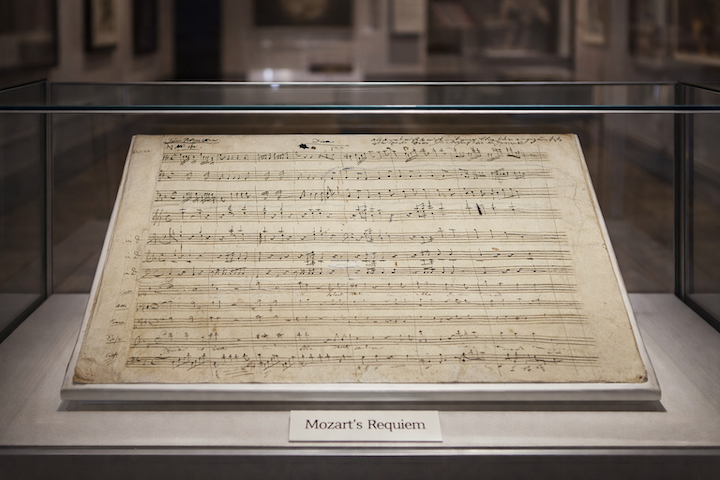

This perspective reaches its most profound expression in the Requiem in D minor. Long mythologized as a premonition of his own death, the Requiem is less a cry of despair than a dialogue between fear and trust. The terror of the Dies Irae is unmistakable, yet it is repeatedly softened by moments of lyrical supplication—Recordare, Lacrimosa—where the soul does not argue for innocence, but begs for compassion.

From a religious standpoint, Mozart’s Requiem reflects a distinctly Catholic theology of mercy over condemnation. Judgment is acknowledged, but it is not the final word. Redemption is not earned through power or purity, but sought through humility.

This same spirit appears in the Great Mass in C minor, where operatic intensity is placed in service of spiritual longing. The music suggests a God who is not distant or abstract, but intimately engaged with human suffering. Faith, here, is not certainty—it is yearning.

Perhaps most revealing is Ave verum corpus, written just months before Mozart’s death. Stripped of grandeur, it offers a quiet meditation on incarnation and sacrifice. There is no drama, no fear—only acceptance. The divine enters the world not in triumph, but in fragility.

Mozart’s sacred music ultimately refuses to separate theology from lived experience. Death is not denied. Suffering is not aestheticized. Instead, music becomes a form of prayer—not one that explains mortality, but one that dwells within it, trusting that grace exists precisely where human strength ends.

His sacred works do not thunder with dogma but plead with humility.

By his final years, Mozart’s music had grown darker, leaner, and more inward. The last symphonies, the Clarinet Concerto, The Magic Flute, and the unfinished Requiem all bear the mark of an artist stripping away ornament to reach essence.

Death, Poverty, and the Birth of a Myth

Mozart died in Vienna in December 1791, aged thirty-five. He was buried in a common grave—not from disgrace, but in accordance with Viennese custom. His death certificate lists a febrile illness; modern medicine suggests infection or inflammatory disease. What it does not support is murder.

Yet myth rushed in where certainty ended.

What Amadeus Gets Wrong—and Why It Persists

The enduring popularity of the film Amadeus has done much to introduce Mozart to modern audiences—and much to distort him. The film’s central conceit, that Mozart was poisoned by Antonio Salieri, belongs not to history but to drama.

There is no credible evidence that Salieri harmed Mozart. The rumor emerged decades later, amplified by Romantic-era fascination with tortured genius and later dramatized for the stage and screen. In reality, Salieri was a successful composer and respected teacher. Their relationship was professional, not homicidal.

Amadeus is best understood not as biography, but as allegory: a meditation on mediocrity confronted with genius, on divine talent bestowed without moral guarantee. It tells us more about envy than about Mozart.

Mozart, Restored to Himself

To reclaim Mozart from myth is not to diminish him. On the contrary, it restores his courage. He was not a laughing fool struck down by jealous rivals, but a relentless craftsman who worked at terrifying speed, revised obsessively, and struggled—financially and emotionally—in a world that admired him without fully supporting him.

His achievement is not that he composed effortlessly, but that he composed honestly: music that refuses to simplify human experience, even when wrapped in elegance.

More than two centuries on, Mozart remains unsettlingly alive. His music does not console so much as accompany us—through joy, confusion, love, and loss—speaking with a voice at once intimate and eternal.

-Nguyễn Tường Khanh-