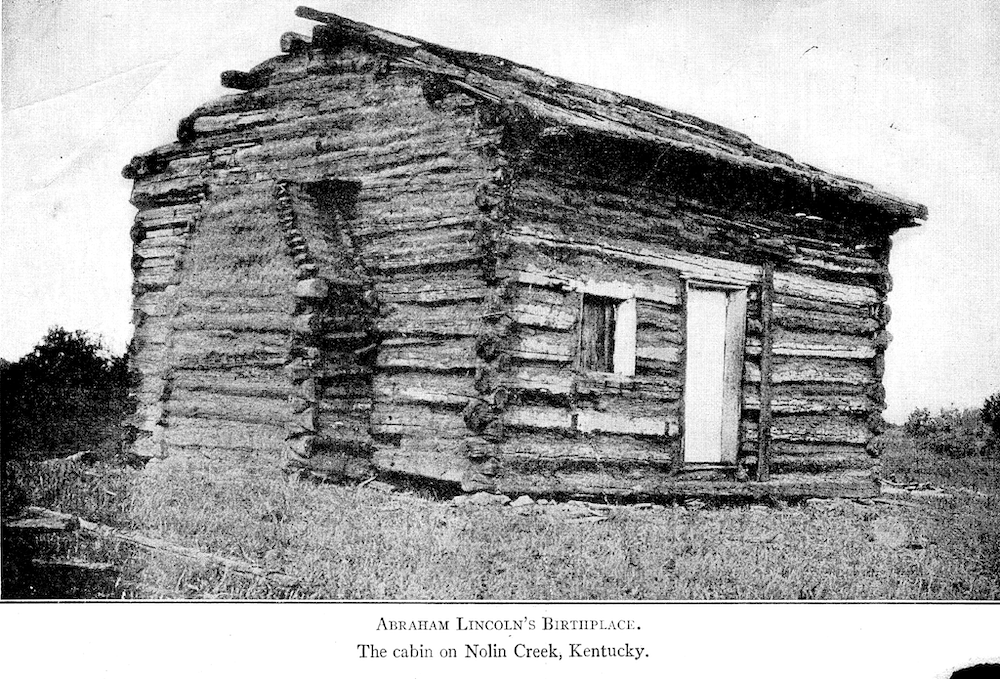

Early Life & Frontier Roots: Abraham Lincoln was born February 12, 1809, in a one-room log cabin in Hardin County, Kentucky (now LaRue County). His upbringing was defined by hardship, manual labor, and self-reliance—conditions typical of the American frontier but formative in shaping his political philosophy. His family moved repeatedly, first to Indiana and later to Illinois, seeking fertile land and stability.

Lincoln’s mother died when he was nine; his stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston, encouraged his intellectual curiosity. Despite less than a year of formal schooling, Lincoln became largely self-educated—reading Shakespeare, the Bible, Blackstone’s legal commentaries, and political texts by candlelight. His early jobs included rail-splitting, storekeeping, surveying, and postmaster duties—roles that exposed him to everyday citizens and later informed his populist political appeal.

Lincoln’s mother died when he was nine; his stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston, encouraged his intellectual curiosity. Despite less than a year of formal schooling, Lincoln became largely self-educated—reading Shakespeare, the Bible, Blackstone’s legal commentaries, and political texts by candlelight. His early jobs included rail-splitting, storekeeping, surveying, and postmaster duties—roles that exposed him to everyday citizens and later informed his populist political appeal.

Education Without Schooling

Lincoln’s intellectual development was autodidactic. He borrowed books whenever possible and practiced writing on wooden boards when paper was scarce. His analytical reasoning and rhetorical precision later became hallmarks of his legal and political careers. By his twenties, he had taught himself law and passed the Illinois bar examination in 1836, launching a successful legal practice grounded in logic, fairness, and persuasive storytelling.

Entry Into Politics

Lincoln entered public life in 1834 as a member of the Illinois State Legislature, initially affiliated with the Whig Party. His early political positions emphasized infrastructure development, banking reform, and economic modernization. After the Whigs dissolved, he became a founding member of the Republican Party, aligning with its anti-slavery expansion platform.

His debates with Stephen A. Douglas during the 1858 Senate race elevated him nationally. Though he lost that election, his moral clarity and eloquence—especially his famous assertion that “a house divided against itself cannot stand”—cemented his reputation as a rising national figure.

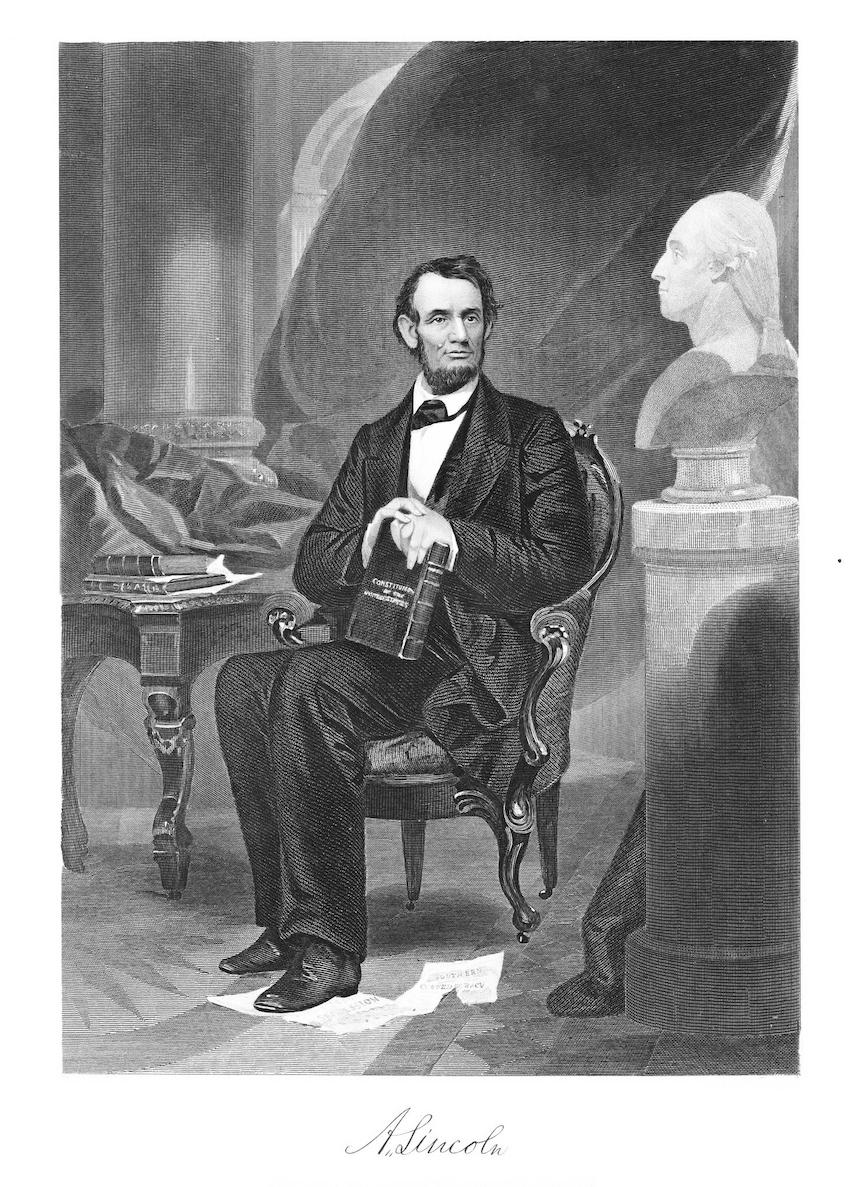

The Presidency & Election Mandate

Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860 with only about 40% of the popular vote but a decisive Electoral College victory, reflecting the fractured political climate of the time. His election triggered secession by Southern states and the onset of the Civil War.

He was re-elected in 1864 during wartime—a rare political feat demonstrating public confidence in his leadership. His administration balanced military strategy, political diplomacy, and constitutional interpretation while preserving the Union.

Philosophy of Republicanism & Governance

Lincoln’s republican ideology centered on three principles:

- Union Preservation: He believed the United States was a perpetual union, not a voluntary confederation.

- Rule of Law: He saw the Constitution as a living covenant protecting liberty.

- Moral Democracy: Lincoln argued democracy required equality of opportunity, even if social equality remained contested.

He was pragmatic rather than ideological. He adjusted policies as circumstances evolved, which critics sometimes called inconsistency but historians now view as adaptive leadership.

The Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation

Issued January 1, 1863, the proclamation declared enslaved people in Confederate states free. Although limited in immediate enforcement, it transformed the Civil War from a conflict about union into one about human freedom. Strategically, it:

- Undermined the Southern economy

- Prevented European powers from supporting the Confederacy

- Allowed Black soldiers to join Union forces

It became one of the most consequential executive orders in U.S. history.

Political Reputation

Lincoln’s contemporaries saw him in sharply divided ways:

Admired for

- Moral clarity

- Humor and storytelling

- Empathy toward common citizens

Criticized for

- Expanding executive power

- Suspending habeas corpus

- Slow initial movement on abolition

Modern historians consistently rank him among the top U.S. presidents for preserving the Union and redefining liberty.

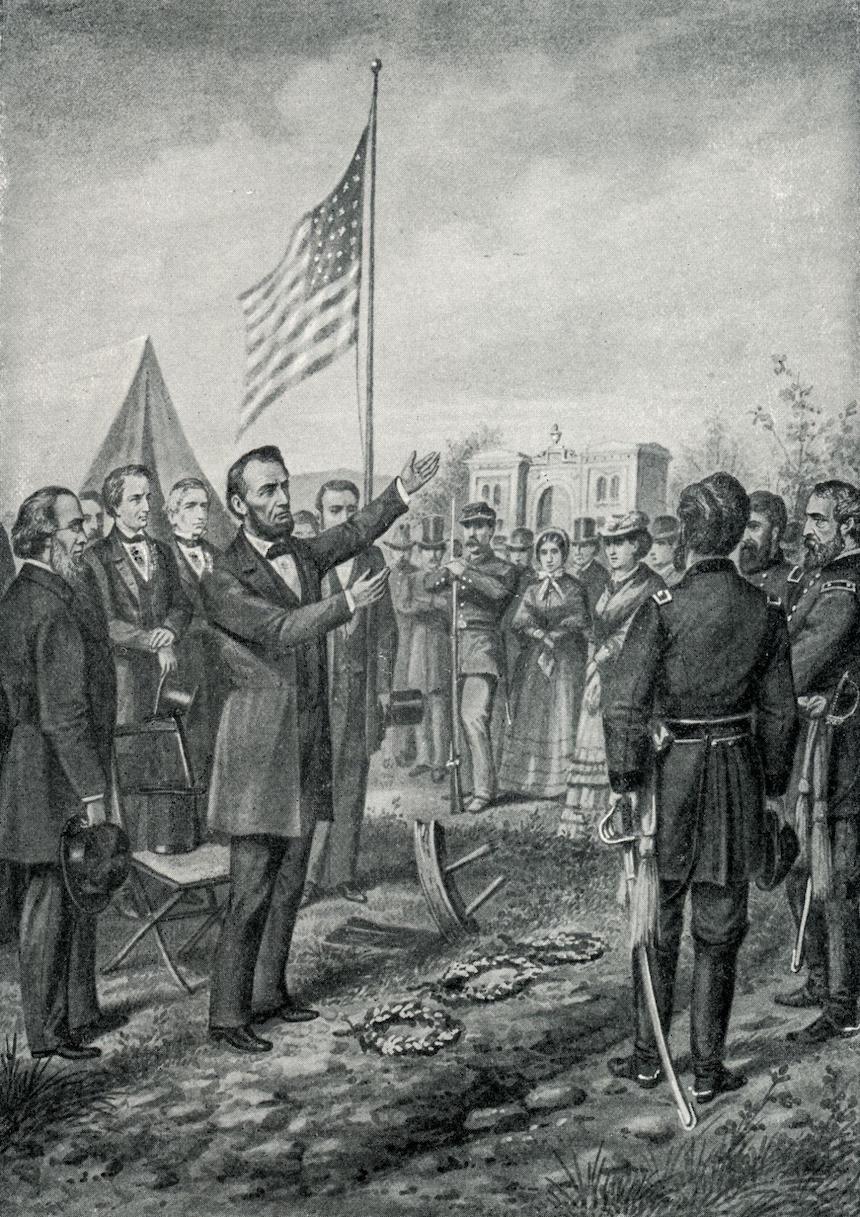

Assassination & National Shock

On April 14, 1865—just days after Confederate surrender—Lincoln was shot by actor John Wilkes Booth while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre. He died the following morning, becoming the first U.S. president assassinated. His death stunned the nation, transforming him instantly from wartime leader into martyr of democracy.

Burial & The Strange History of His Remains

Lincoln was buried in Springfield, Illinois. His coffin, however, was moved or opened multiple times—often cited as 17—due to:

- Construction of new tomb structures

- Verification of identity after grave-robbery attempts (notably in 1876)

- Security relocations to prevent theft

In 1901 his coffin was encased permanently in concrete beneath tons of stone, ending further disturbance.

Legacy — Why Lincoln Still Matters

Lincoln’s enduring significance lies in how he reshaped the moral and constitutional identity of the United States.

He is remembered for:

- Preserving the Union

- Ending slavery’s legal foundation

- Elevating democratic ideals globally

- Demonstrating humility in leadership

- Delivering immortal speeches such as the Gettysburg Address

His image appears on Mount Rushmore, the U.S. penny, and the five-dollar bill. More importantly, he remains a symbol of principled leadership under crisis—a benchmark against which future presidents are judged.

Lincoln is not simply remembered as a president, but as the architect of a “second founding” of the United States—one that redefined freedom, citizenship, and the meaning of equality.

-Nguyễn Bách Khoa-

Sources for Further Reading

Primary Historical & Scholarly Resources

- Library of Congress — Abraham Lincoln Papers Collection

- National Archives — Civil War and Lincoln administration records

- Smithsonian Institution — Lincoln historical analyses and artifacts

- Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum — Research archives

- National Park Service — Lincoln Home & Ford’s Theatre historical reports

Academic & Scholarly Works

- Team of Rivals by Doris Kearns Goodwin

- Lincoln by David Herbert Donald

- Battle Cry of Freedom by James M. McPherson

- Oxford University Press — American National Biography entry on Lincoln

Digital History & Educational Institutions

- Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History — Civil War documents

- Yale Law School Avalon Project — Emancipation Proclamation text

- Cornell University Legal Information Institute — Constitutional context