The Vietnam War left behind a series of iconic images that captured the most harrowing moments of a conflict that reshaped a nation—and the world. From the start of the war to its chaotic end, three photographs in particular came to define its legacy: Eddie Adams’ haunting image of a South Vietnamese officer executing a Viet Cong prisoner on the streets of Saigon during the Tet Offensive; Nick Ut’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of a terrified, naked girl fleeing a napalm attack; and Hugh Van Es’ frame of desperate evacuees scrambling onto a rooftop helicopter on April 29, 1975, just one day before the fall of Saigon. These images, etched into global memory, are more than visual records—they are lasting symbols of trauma and transformation.

For many Vietnamese, these photos remain painful reminders of a national nightmare. An estimated 255,000 Vietnamese escaped as boat people, arriving in new homelands across the globe. Thousands more perished at sea, disappeared on land, or remain unaccounted for. Today, over two million Vietnamese live in the United States. According to Wikipedia, roughly four million Vietnamese reside overseas—most of whom left after the war ended in 1975.

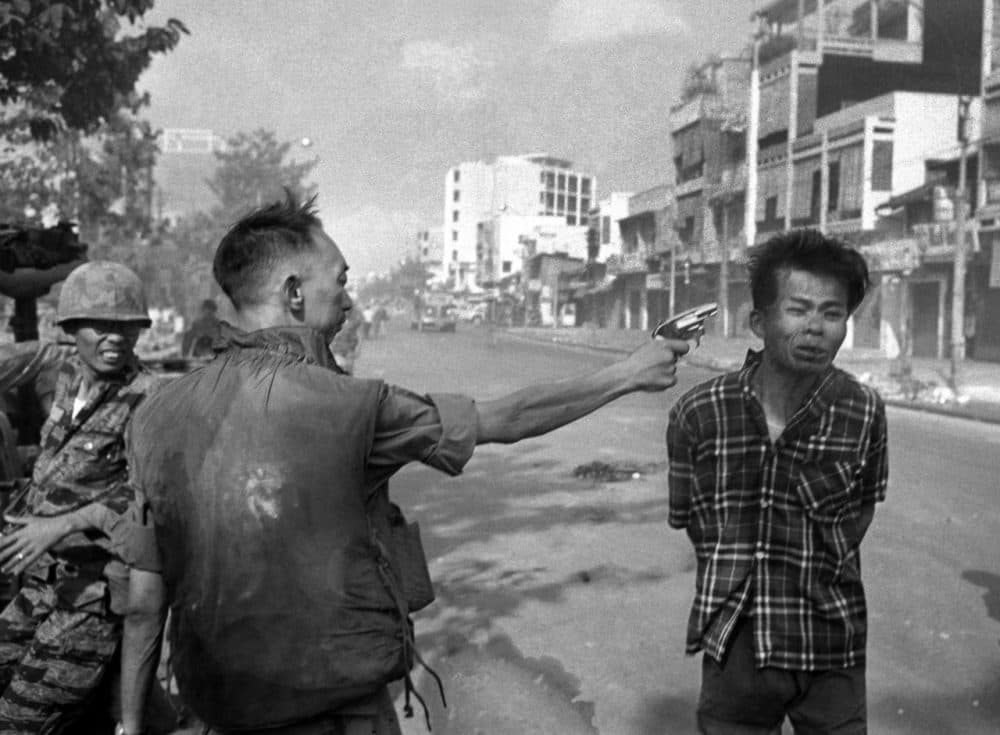

Tet Offensive, 1968 – The Shot That Echoed Around the World

Eddie Adams’ famous photograph of General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan executing a Viet Cong prisoner shocked the world. But Adams would later write in Time magazine: “The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera.” Adams came to regret taking the photo. He explained, “Photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world. People believe them—but photos can lie, even without being doctored. They show only half the truth.”

What the photo didn’t show, Adams explained in an interview with NPR, was that General Loan had just captured a man who had allegedly murdered one or more American soldiers and South Vietnamese personnel during what was supposed to be a Tet holiday ceasefire. Adams came to view the general not as a villain, but as a patriot, a man pushed to the edge in a brutal war.

Years later, after Loan had resettled in the U.S. and suffered immensely because of the photo’s notoriety, Adams personally apologized to him and his family for the damage the image caused. When General Loan died in Virginia, Adams sent flowers with a note that read, “I am sorry. Tears are in my eyes.”

The photo also intensified the American antiwar movement. Just two months after it was published, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced he would not seek re-election. Who could have predicted that one image would help shift public opinion so dramatically and contribute to the eventual fall of South Vietnam?

The Napalm Girl, 1972 – The Cry for Peace

On June 8, 1972, Associated Press photographer Huỳnh Công “Nick” Út was covering clashes along Highway 1 near Tây Ninh. Caught in a traffic jam caused by Viet Cong forces blocking the road, he joined a South Vietnamese infantry unit. Around 1 p.m., the troops called in airstrikes. Skyraider planes dropped bombs and napalm near a Cao Đài temple, setting the area ablaze.

In the chaos, villagers—clothes burned, faces twisted in fear—ran toward the journalists. Út recalled, “Suddenly I saw a little girl, naked and screaming, running toward me. She took off the burning clothes. She was crying for her brother. I took the photo, then rushed to help her.”

The girl was nine-year-old Phan Thị Kim Phúc. Burned terribly, she cried out, “It’s too hot! Too hot!” Út gave her water, carried her to his car, and drove an hour to a hospital in Củ Chi. “They weren’t going to treat her,” Út said. “So I told them, ‘I’m a journalist. If she dies, I don’t want to see it happen.’ They finally agreed to help.”

Kim Phúc spent 14 months in the hospital and endured 17 surgeries. Though she returned to her hometown of Trảng Bàng, her life would never be the same. Her photo was used by Hanoi’s propaganda machine during the war’s final years. In later interviews, Kim Phúc shared that she had contemplated suicide, feeling lost and exploited. Eventually, she found solace in Christianity after reading the Bible and converted from Cao Đài to Catholicism.

In 1986, Kim Phúc was sent to Cuba for medical treatment and education. While on her honeymoon in 1992, she and her husband defected during a stopover in Newfoundland, Canada, and sought asylum. Today, they live in Ontario with their two children. She hopes the world sees her image not as a symbol of pain, but as “a cry for peace.”

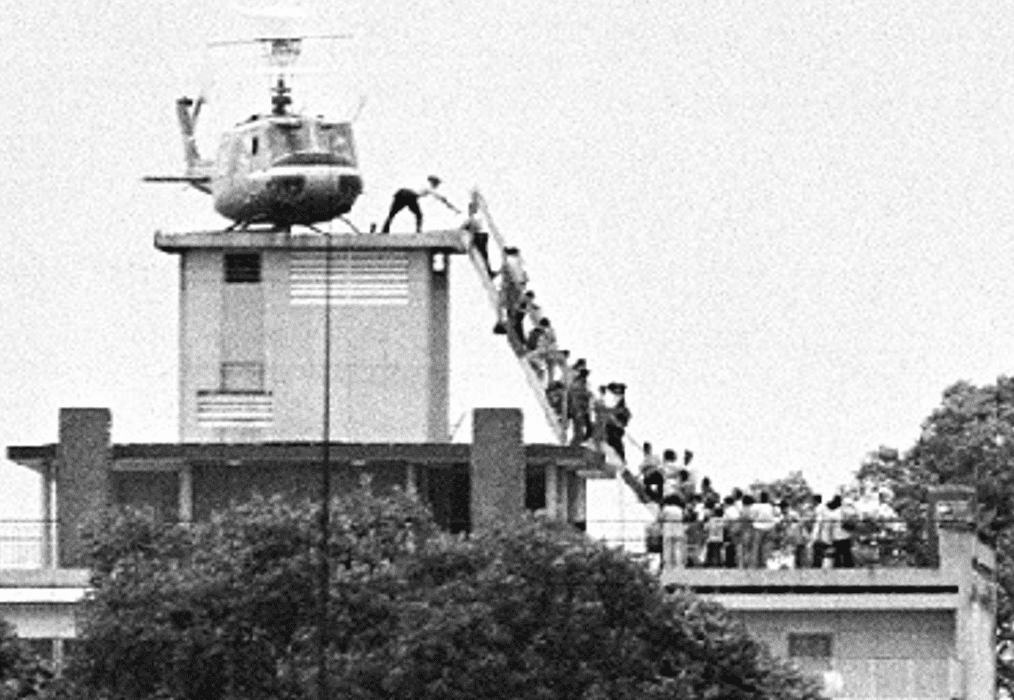

The Rooftop Evacuation, April 1975 – The End of Saigon

On April 29, 1975, Dutch photojournalist Hugh Van Es stood on a Saigon balcony with his Nikon and a 300mm lens. He captured an image of a helicopter atop an apartment building—evacuating Vietnamese civilians. That photo became the defining image of America’s largest helicopter evacuation in history, and of the fall of Saigon.

For decades, people mistakenly believed the photo was taken on the roof of the U.S. Embassy. In fact, it was a nearby CIA safehouse. The next day, South Vietnam ceased to exist.

Thirty years later, Van Es returned to Vietnam to revisit old battlegrounds like Hamburger Hill. At the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City, he saw one of his own photos miscaptioned as showing American troops “fleeing.” In truth, they were advancing. When he asked for a correction, museum officials refused. “I took those photos for future generations—for history,” Van Es said. “I will not allow them to be distorted for propaganda.”

The War’s Long Shadow, 1975–2025

Eddie Adams died in 2004, Van Es in 2009. Nick Út remained with the Associated Press for years after his famous shot. The U.S. lifted its embargo on Vietnam in 1994, normalized diplomatic relations in 1995, and signed a trade agreement in 2001. Yet 1,319 American soldiers remain missing in Vietnam, out of 1,731 across Southeast Asia.

Many U.S. and Vietnamese cities have since become sister cities—San Francisco with Ho Chi Minh City, Newport Beach with Vũng Tàu, Seattle with Hải Phòng, Pittsburgh with Đà Nẵng. But not all Americans embrace these partnerships. In Fayetteville, North Carolina, home to Fort Bragg, many veterans—especially from the 82nd Airborne Division—were upset that their city paired with Sóc Trăng, where some had served during the war.

Books and documentaries have helped peel back the layers of propaganda and memory, offering new perspectives on the conflict. Titles like The Winning Side, The Lightbulb, Vietnam Wikileaks, The Defeated, and When Allies Abandon join films like The Last Days in Vietnam and Ride the Thunder in offering alternative views to Hollywood portrayals like Full Metal Jacket and Apocalypse Now.

A Nation Divided by Memory

The war’s toll was staggering: 58,220 American soldiers, and between 1.5 to 3.6 million Vietnamese lives lost, including civilians. After 1975, an estimated 200,000 people were sent to reeducation camps; many later resettled in the U.S.

Former South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu famously said, “Don’t listen to what the Communists say, watch what they do.” Meanwhile, Northern leader Lê Duẩn once declared, “When we entered the South, we were fighting for China and the Soviet Union.” Perhaps the most truthful reflection came from a Hanoi official who said, “April 30 was a day when millions celebrated, and millions mourned.”

Fifty years after the war’s end, reconciliation remains elusive. In America, overseas Vietnamese communities continue to commemorate April 30 as a Day of Mourning—wearing black, holding vigils, and singing songs of longing. Meanwhile, in Vietnam, April 30 is celebrated as Reunification Day, with parades and banners from north to south—even as long lines persist outside U.S. consulates from people hoping to leave.

-Đức Hà-

Exclusive for HuuTri.org