I was 21, barely finding my voice in crowded lecture halls and late-night study groups at my American college, when I boarded a flight to Poland. The plan was simple—backpack across Eastern Europe, devour pierogis, snap pictures of Baroque buildings, and feel something new. But I never expected that a quiet, unassuming apartment in Warsaw would change me.

It was a gray autumn afternoon when I found myself standing in front of the modest building on Freta Street in Warsaw’s New Town. Tucked between souvenir shops and cafés was the Maria Skłodowska-Curie Museum—the very place where Marie Curie, the trailblazing physicist and chemist, was born and later returned after tragedy struck.

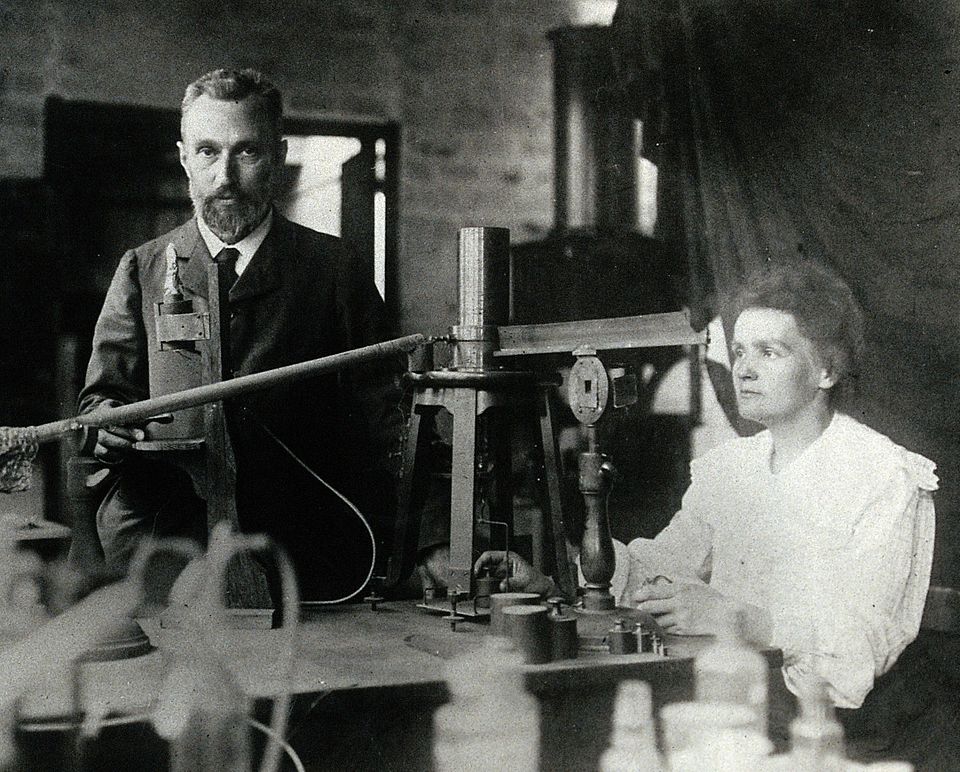

Inside, the air was thick with reverence. The walls whispered stories. I walked slowly through the rooms, reading faded letters, peering at instruments she once touched. One room led to a small balcony. Legend has it, after her husband Pierre Curie died in an accident in Paris in 1906, Marie returned to Warsaw. Here, in this very apartment, she would often stand on that narrow balcony—silent, gazing at the Warsaw sky for hours. Locals said she didn’t speak to anyone for years. Some thought she was lost in grief. Others believed she was still speaking to Pierre.

I stared at the same sky. My fingers ran along the cold iron of the balcony’s railing. And for a moment, I felt the weight of her sorrow—and her brilliance.

A Life That Defied Limits

Marie Curie was born Maria Skłodowska in 1867 in Warsaw, in what was then Russian-controlled Poland. She grew up in a society where women were not encouraged to attend university. That didn’t stop her. She moved to Paris at 24, changed her name to Marie, and enrolled at the Sorbonne. It was there she met Pierre Curie, a fellow scientist who would become her partner in life and in science.

Their work on radioactivity—a term Marie herself coined—would alter the course of modern science. But it wasn’t easy. Because she was a woman, Marie often had to publish her research jointly with Pierre to gain credibility. She even had to submit her early papers under his name, despite being the primary researcher.

In 1903, Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize—in Physics, shared with Pierre and physicist Henri Becquerel. After Pierre’s death, she continued their research alone, and in 1911, she won her second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry, for her discovery of the elements polonium and radium. She remains the only person to win Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields.

Yet, despite her brilliance, the French scientific establishment remained cold. She was denied membership to the prestigious Académie des Sciences. Rumors swirled about her private life. And through it all, she kept working—often in unsafe conditions, unaware of the long-term effects of radiation exposure.

Love, Legacy, and Loss

Marie and Pierre had two daughters: Irène and Ève. Irène followed closely in her mother’s footsteps. A physicist herself, she—along with her husband Frédéric Joliot-Curie—won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935. It made the Curies the most decorated scientific family in history. Ève, on the other hand, chose a different path—she became a writer, journalist, and humanitarian, penning a best-selling biography of her mother titled Madame Curie.

Marie Curie eventually returned to France after her years in Warsaw. She continued her groundbreaking research until her health declined. In 1934, she died of aplastic anemia, a condition likely caused by prolonged exposure to radioactive materials. She was buried next to Pierre in Sceaux, but in 1995, their remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris, making Marie the first woman honored there for her own achievements.

A Personal Reckoning

As I left the museum that day, the wind rustled the trees lining Freta Street. I couldn’t stop thinking about what it must have felt like to be a woman in her time—brilliant, determined, and constantly dismissed. I thought about my own challenges, how even in modern classrooms, I sometimes hesitate to speak, fearing I might sound “too confident,” “too assertive,” or worse, “too smart.”

Marie Curie didn’t just break barriers—she dissolved them. And yet, behind every success was a society trying to minimize her, a gate she had to kick open, a credit she had to fight for. The very air I breathed in Warsaw felt changed—charged with the silent power of every woman who had ever been underestimated.

And as I walked away from the apartment, I glanced up at the balcony once more. The sky was turning pink. Maybe she had spoken to Pierre. Or maybe, she had spoken to the universe itself—challenging it to make room for a woman who dared to know more.

If you ever find yourself in Warsaw, don’t just visit the tourist sites. Find that apartment on Freta Street. Stand on the same floorboards where a young woman once stared down a world that told her she didn’t belong—and changed it anyway.

-Nguyễn Phương Anh-