On a cold January day in 1809, a child was born into a life already marked by disappearance. His parents were actors—figures who lived by illusion—and before he could form memories of them, they were gone. Orphaned before the age of three, Edgar Allan Poe would grow up haunted by absence, a condition that would later become the emotional architecture of his work.

Taken in by the prosperous Allan family of Richmond, Virginia, Poe was raised on the edge of privilege without ever fully belonging to it. John Allan provided for his education but withheld affection and legitimacy. Poe absorbed classical literature, poetry, and languages with ease, yet his temperament clashed with Allan’s mercantile pragmatism. At the University of Virginia, brilliance and self-destruction emerged side by side: academic excellence shadowed by gambling debts, followed by abandonment.

Taken in by the prosperous Allan family of Richmond, Virginia, Poe was raised on the edge of privilege without ever fully belonging to it. John Allan provided for his education but withheld affection and legitimacy. Poe absorbed classical literature, poetry, and languages with ease, yet his temperament clashed with Allan’s mercantile pragmatism. At the University of Virginia, brilliance and self-destruction emerged side by side: academic excellence shadowed by gambling debts, followed by abandonment.

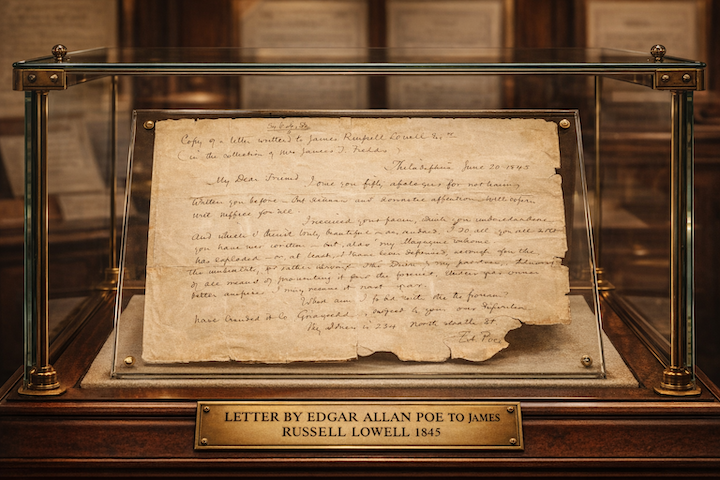

What followed was a restless apprenticeship—military service, expulsion from West Point, and a plunge into the precarious world of literary magazines. Poe did not merely write; he dissected. As an editor and critic, he was exacting, unsparing, and often feared. He believed literature should be precise, unified, and intellectually honest. This conviction won him admiration and enemies in equal measure.

Fame arrived suddenly in 1845 with The Raven. Overnight, Poe became a public figure, reciting the poem to captivated audiences. The black bird croaking “Nevermore” perched itself permanently in the American imagination. Yet fame did not bring comfort. Poe remained poor, ill, and burdened by grief, living proof that literary immortality and financial security do not necessarily meet.

Poe’s marriage to his cousin Virginia Clemm, when she was thirteen and he twenty-seven, has long unsettled modern readers. In the context of the 19th century, such unions—particularly among cousins—were not unheard of, but context does not erase discomfort. What is clear is that Virginia became the emotional center of Poe’s fragile domestic world. Her long decline from tuberculosis was a slow catastrophe. Watching her fade left an indelible mark on his imagination. After her death at twenty-four, Poe’s writing grew even more spectral, saturated with the idea he himself articulated: “the death of a beautiful woman” as the most poetic of subjects.

Was The Raven autobiographical? Poe insisted it was not. He described it as a carefully engineered poem, constructed to achieve a single emotional effect. And yet, its relentless grief, its refusal of consolation, reads like the voice of a man who knew too well what it meant to love and lose beyond recovery. The poem may not be a diary, but it is unmistakably intimate.

During his lifetime, Poe was admired and distrusted in equal measure. Critics accused him of morbidity, of moral emptiness, of an unhealthy fascination with madness and death. Others recoiled from his personality—acerbic, proud, and unwilling to flatter. He made no effort to soften his judgments, and the literary establishment did not forgive him for it. After his death, a rival ensured that Poe’s reputation would be stained with tales of vice and instability, myths that lingered long after the facts had faded.

Even fellow writers were divided. Mark Twain, for instance, found Poe’s work excessively dark, lacking the human warmth Twain prized. He mocked Poe’s gloom while conceding his technical skill. It was a disagreement of sensibility rather than stature—two visions of American literature passing each other without converging.

So was Poe a poet or a prose writer? In his own time, he was known primarily as a poet. Poetry made him famous; prose paid the bills. In posterity, the balance has shifted. His short stories—of detection, terror, and psychological collapse—laid the foundations for entire genres. The modern detective story, the psychological thriller, and much of speculative fiction trace their lineage back to Poe’s insistence on logic, structure, and inner terror.

Poe died in Baltimore in 1849 under circumstances still unresolved, found delirious and alone. He was forty years old. No consensus exists on what killed him, and perhaps that uncertainty is fitting. Poe remains a figure suspended between fact and legend, reason and nightmare.

What endures is not the mystery of his death, but the clarity of his vision. Poe believed literature should be exact, purposeful, and emotionally total. He lived at the margins of society, but he wrote with surgical precision. In doing so, he transformed darkness into form—and secured his place as one of the most singular voices in American letters.

-Lê Nguyễn Thanh Phương-